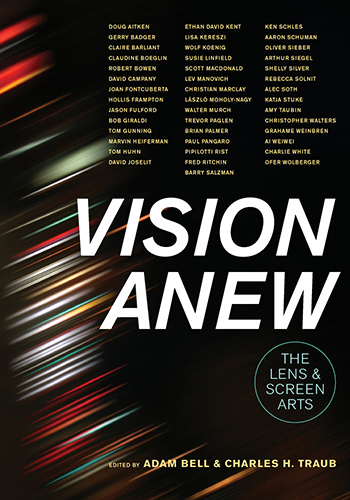

Vision Anew

Adam Bell and Charles H. Traub, editors

University of California Press 2015

Reviewed by Leo Hsu

Edited by SVA faculty members Adam Bell and Charles Traub, Vision Anew: The Lens and Screen Arts grapples with the state of contemporary photography: its anxieties and its possibilities. The idea that photography may be changing in some essential way, according to a previously unknown trajectory, produces both apprehension and excitement. “[Our] obsession with photography’s demise and progression is as closely tied to notions of modernist artistic and technological progress as it is to the medium’s technological nature,” writes Bell in the preface of the book. “If the tools keep changing,” Bell notes, “so too must the art. In the end the anxiety always reveals more about ourselves than it does about the medium.”

Vision Anew is a sort of follow-up to The Education of a Photographer, the 2006 reader that Traub and Bell edited with Steven Heller. Both books reconsider the history of photography in light of current directions. But where Education presented the field of photography in terms of a “modernist artistic and technological progress,” Vision Anew offers a view that is less certain, where borders are less-clearly demarcated, and explores more extensive frameworks for thinking about photography. In Vision Anew, Traub and Bell have brought a substantial body of essays together that range across disciplines, and that often speak in different idioms, coming from theorists, historians, and practitioners. The readings aren’t necessarily the best known or most representative writings by the contributors, but assembled here they present, broadly, a case.

In compiling Vision Anew, Straub and Bell faced a challenge: how do you address “photography” as a technology, a medium, a tradition or a community of practice, recognizing continuity between past and present, while simultaneously expanding upon its traditional definitions? Film and photography have historically enjoyed their own disciplines and canons of knowledge. How can they be brought together, along with research and practice around social media? Their solution was to organize Vision Anew in three sections: “From the Lens”, “Vision and Motion”, and “Old Medium/ New Forms”, with each group of readings suggesting a particular set of questions. Each of these sections could be used readily as a seminar syllabus.

“From The Lens” addresses the history of photography and reconsiders well-entrenched views. A chapter from Ken Schles’ (very difficult to come by) A New History of Photography reflects on Schles’ own internalization of a history of images, and its influence on his work. Susie Linfield’s “A Little History of Photography Criticism, or Why do Critics Hate Photography” from The Cruel Radiance should be required reading for all students of photography, and serves as a reminder that photography criticism should be read as historical and discursive. Marvin Heiferman’s call for contemporary visual literacy foreshadows a concern with new media technologies and society that is developed in the third section of the book.

Essays in this first group also suggest a move away from the questions around how photography represents vision or perception “realistically” (or, as Walker Evans might say, “plausibly”, as discussed in Gerry Badger’s contribution), which dominated discourses in the 20th century. Robert Bowen traces the relationship between photography and other technologies emerging in the 19th century such as electricity, reframing the development of photography as part of a broader interest in “light and time”. This theme is picked up by Rebecca Solnit in the first chapter from her book on Muybridge, River of Shadows, in the next section.

The second, sprawling section of the book, “Vision and Motion,” draws connections between photography and film and video, both in the present and historically, again asking us to reconsider received narratives. Many of the readings touch on the relationship between time and motion as related to photography and film. Among these readings are some of the more theory-driven pieces in the volume: David Campany looks at cinema and the freeze frame to ask in what sense film and still photography “freeze” time, drawing from cinema studies and cinema theory; Grahame Weinbren’s essay asks a similar question from a different direction, approaching it through the movement seen in a camera obscura and asking how the perception of motion is translated through perspectival processes; Tom Gunning offers that realism in film can be traced to our empathetic experience of motion, rather than the familiar read on the Peircian indexical relationship between photograph and referent. This theme is clearly underscored, but is not the main argument of the volume. Other issues emerge as well, as the section takes us through conversations with filmmakers and artists, few of whom would be conventionally considered photographers, but whose insights are preoccupied with considerations of the interplay between experience, narrative and time.

The final section, “Old Medium/ New Forms” focuses on the role of photography in novel 21st century media and technology. The contributors are interested in photography as machine-produced, shareable, disposable; pictures that no one will ever see, meaningful as data. Claudine Boeglin and Paul Pangaro ask what journalism looks like in this context, as do Fred Ritchin and Brian Palmer. Lev Manovich notes that we are constrained by what our software allows us to do while Trevor Paglen discusses photography’s disciplinary uses. Charlie White’s contribution looks at authorship and the sharing of “unauthored” macros (lolcats etc.) Lisa Kereszi’s essay considers streetview photography: she beautifully connects Robert Frank’s The Americans and Paul Fusco’s RFK Funeral Train with Doug Rickard’s New American Picture. The section ends with four manifestos, among them Joan Fontcuberta’s provocative and smart “A Post-photographic Manifesto,” possibly available in English for the first time here.

Vision Anew acknowledges and struggles with possibilities that have not yet congealed. The title of the volume highlights the ambiguities that the editors finessed: “lens and screen arts,” with its effort to find a technological conceit for organizing socially meaningful activities, does not fall trippingly off the tongue. But the desire to bring photography, film, and contemporary media arts into conversation together is perhaps more usefully construed neither as convergences nor divergences, but as realignments. As it is, the new relationships between old media are neither clearly defined nor streamlined; they are precarious and various, full of momentum, and sometimes seemingly blind to history. These are the great anxieties of modernity, that the path to progress is unclear, or that the investments that led us to where we are will be forgotten. Bell and Traub suggest that we reassess our baggage, the assumptions to which we’ve become so comfortable. How can the history of photography be written today as to anticipate, if not the future, then at least the present?

Vision Anew: the Lens and Screen Arts includes contributions by: Ai Weiwei, Doug Aitken, Gerry Badger, Claire Barliant, Adam Bell, Claudine Boeglin, Robert Bowen, David Campany, Joan Fontcuberta, Hollis Frampton, Jason Fulford, Bob Giraldi, Tom Gunning, Marvin Heiferman, Tom Huhn, David Joselit, Ethan David Kent, Lisa Kereszi, Wolf Koenig, Susie Linfield, Scott Macdonald, Lev Manovich, Christian Marclay, László Moholy-Nagy, Walter Murch, Trevor Paglen, Brian Palmer, Paul Pangaro, Pipilotti Rist, Fred Ritchin, Barry Salzman, Ken Schles, Aaron Schuman, Olivier Sieber, Arthur Siegel, Shelly Silver, Rebecca Solnit, Alec Soth, Katja Stuke, Amy Taubin, Charles Traub, Christopher Walters, Grahame Weinbren, Charlie White, and Ofer Wolberger

Leo Hsu is a photographer and writer based in Toronto and Pittsburgh.

Contact Leo here.

Support Fraction and purchase Vision Anew: the Lens and Screen Arts here.