Pieces of String

Photographs by Justin Kimball

Essay by Douglas M. Kimball

Softbound with slipcase, 9.5 x 10 inches, 128 pages and booklet, 60 color images

Radius Books, 2012

Reviewed by Lauren Greenwald

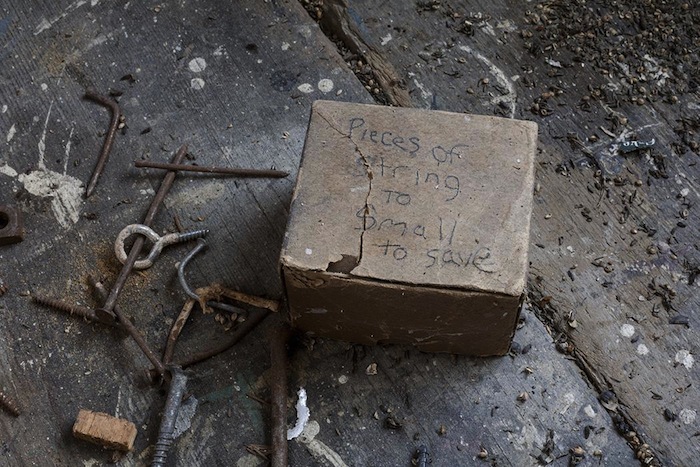

A disintegrating cardboard box bears a hand-scrawled label on its lid: Pieces of string to small to save. Who was the person who acknowledged he should not save these smallish pieces of string, yet carefully stashed them away? Could an image of a small, forgotten object, left on a dirty floor, be a more descriptive record of a person’s life than any obituary?

Justin Kimball’s Pieces of String is a collection of photographs taken over several years throughout New York State and New England, in abandoned homes and buildings being cleared for sale. His brother and collaborator, Douglas Kimball, is an auctioneer, whose job it was to empty these spaces and liquidate their contents. I say collaborator because Douglas contributed the excellent introductory essay for the book, and his acerbic, evocative text is a wonderful counterpoint for the images contained within. He brings a certain gallows humor to his description of his job and his experiences, as he notes, “This is an autopsy of personal possessions, and we are organ harvesters.” There is a profound disconnect between how we view the remnants of our dearly departed, and how a stranger might view them. The heavy burden of sentimentality weighs on the most mundane of objects and spaces for the families, but those who are charged with the business of cleaning up after are necessarily devoid of nostalgia; they have other concerns. Kimball describes himself on a job, absorbed in searching for items of value, “…barely a thought popping through my brain anymore except shiny, shiny.” Like a crow searching the ground, I am distant but precise.”

Enter Justin Kimball, with his camera and his quiet observation, a completely different mission in mind. The homes examined are in many cases run-down, disintegrating spaces filled with the kind of possessions one might imagine of a miserly shut-in who has not left his house in several decades. The layers of detritus and dirt in these images illustrate years of occupation and existence; almost nothing is pristine. Illuminated by daylight, the colors and atmosphere of these places are of a predominantly New England type: cool greens, muted blues and beiges and greys, faded floral wallpaper and weathered wood floors. The images are a series of views, as perceived by the artist; close-ups of small, discarded objects, impromptu tableaux made up of a mantel, a desk, or a counter and the items arranged upon the surfaces, views through dingy windows. While there is no specific narrative binding the image sequence, a few patterns emerge in the images and through their repetition, a sort of rhythm develops. We see a number of views through doorways, into mirrors, and between rooms that compress space into layered planes of color, and a disturbing number of empty beds, most often stripped bare to reveal their striped mattresses. I found these images the most affecting; the beds exist in varying levels of tidiness, or even decay, as one decomposing mattress has begun to sprout leaves. My personal favorite is plate 16, in which a tiny, cluttered room, illuminated by a single shaft of sunlight, contains a rumpled, stained cot surrounded by piles of old newspapers and books. I imagine the days, months, even years its occupant spent lying there, and I want to know more, but I suspect it will be a sad, troubling story. Very few of the images actually give clues to an identity, but one of the last images in the book captures a long, handwritten note on a door next to a sticker which reads, Security Check by Sheriff’s Office. Reading the note, the viewer suddenly comprehends the fate of this house’s occupant.

At this point, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the physical appearance of the book itself. Accompanied by the essay printed as a separate pamphlet, the softbound book contains 60 color images, gorgeously printed, for the most part presented as single images opposite a pristine white page, and interspersed with a few enlarged images spanning both pages of a spread. It comes cleverly wrapped in a pale trifold slipcase held firmly shut by a wide, industrial rubber band, such as one used as a tourniquet for drawing blood. I confess, the packaging was a bit too clever for me; at first glance, it looked as if the hardbound case was damaged, seemingly marred with scuffs, scratches, and water stains – had it been left carelessly on a table, subjected to spills and stains? It turns out this is deliberate, and Radius Books has outdone themselves again with a memorable package design. Evoking the subject matter of the book, the cover itself suggests a remnant; a forgotten and abused object rather than a pristine new publication.

In reviewing this book, I found myself returning to it again and again, and with every new reading I discovered something new, adding another layer to my experience and perception. The book is seductive, distressing, and utterly engrossing. Try as I might to view this dispassionately, I am deeply affected by these tracks and traces of unknown individuals. As Douglas Kimball wrote in his essay, “The strata of existence are an anthem to the end, a string of repeated activities that strip the heart to see.”

Support Fraction and buy the book here.

Lauren Greenwald is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Photography at NMSU and currently splits her time between Las Cruces, NM and Albuquerque, NM

To learn more about Lauren, please visit her website.