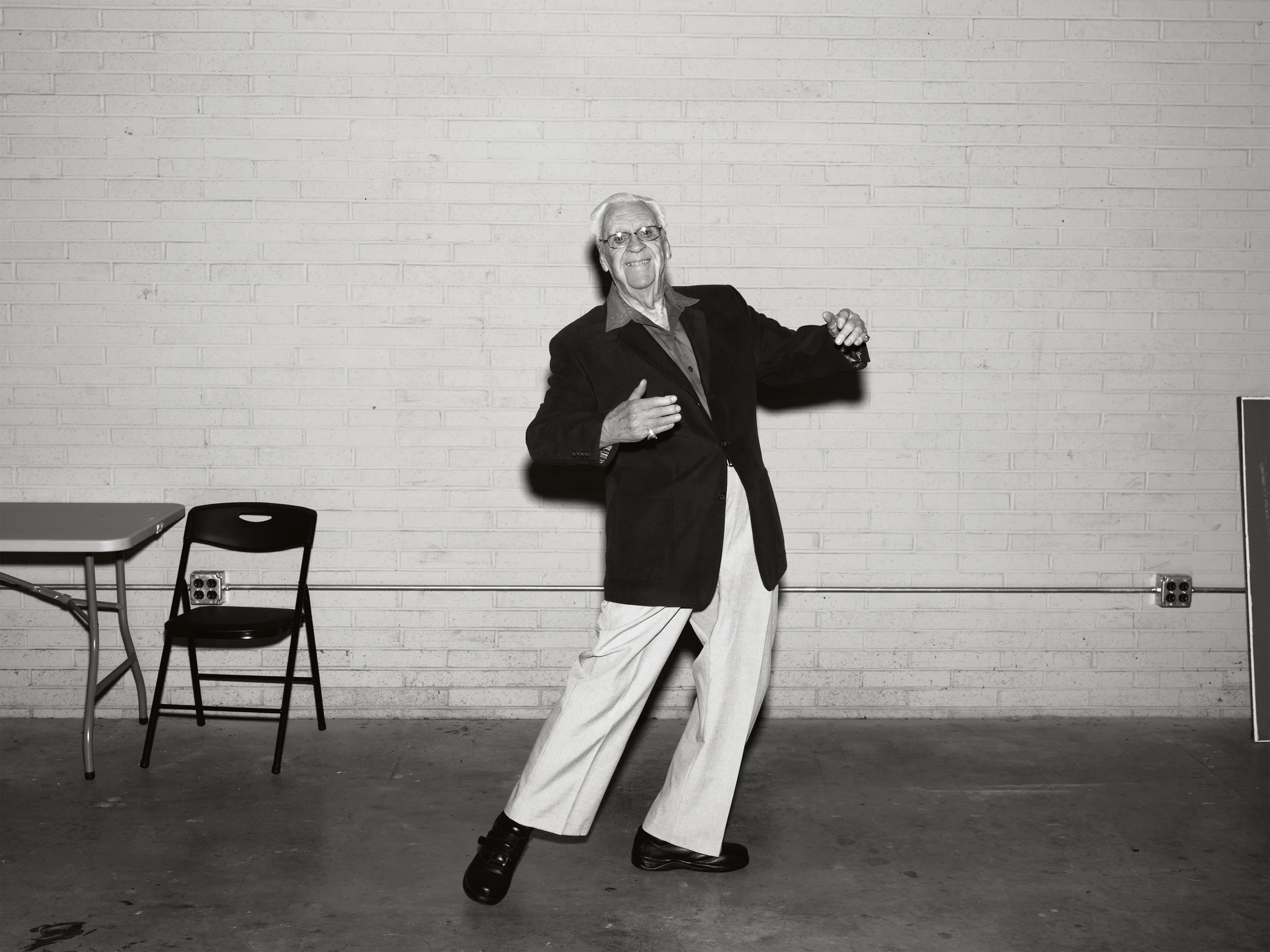

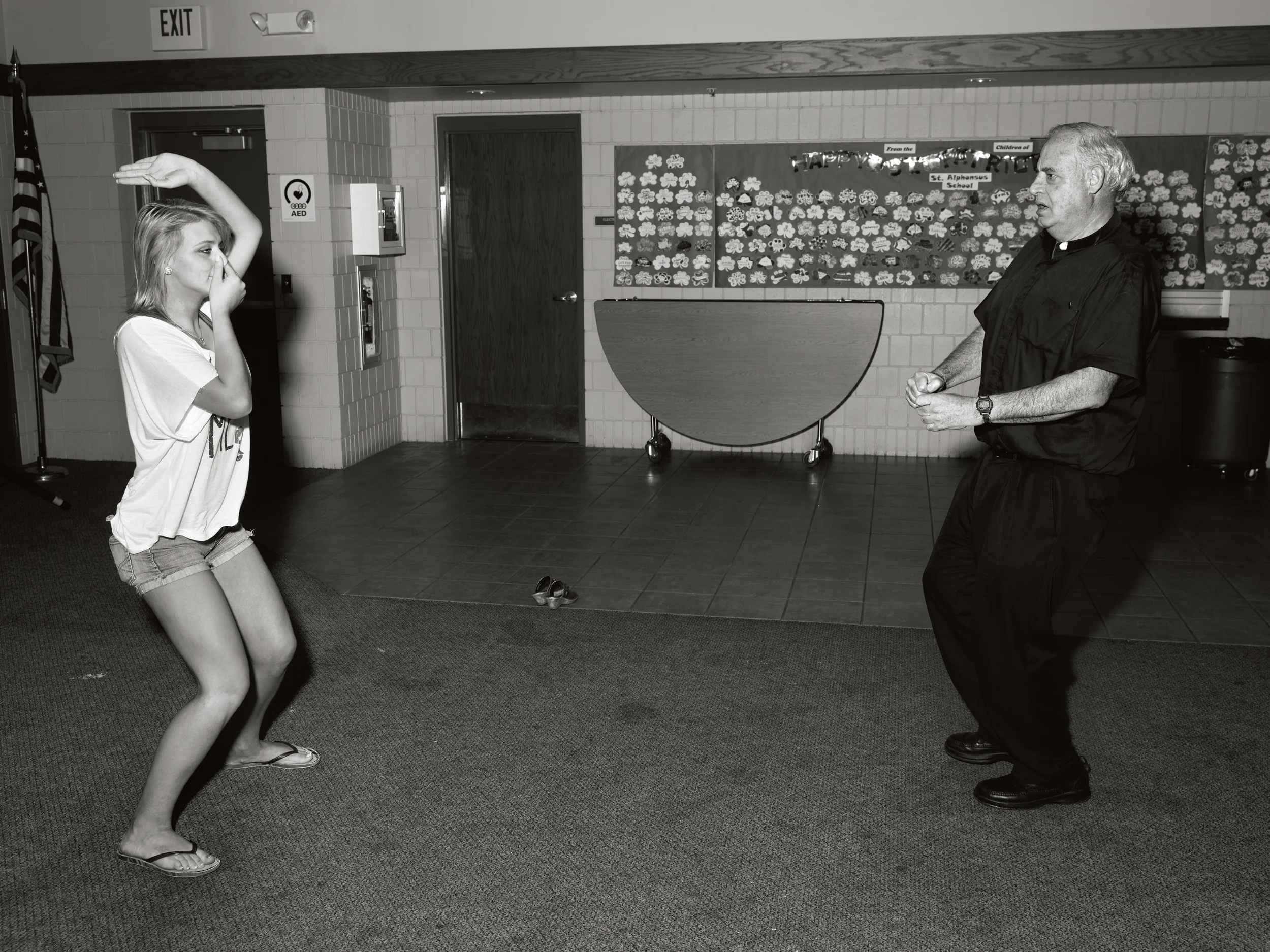

Alec Soth’s Songbook travels the reader across and around the United States, following a kind of dream logic. The book begins with a prologue of five pictures that depict people engaged in music or performance. They are fully absorbed in their moments, the focus evident in their faces even as Soth’s pictures supply an abundance of detail about their mundane settings. The series sets out a proposition: we experience joy in ordinary places when we allow ourselves to fully inhabit them. By being where we are, Soth offers, we may be transported.

In the images that follow this initial run the mood darkens, becoming increasingly lonely and surreal. The sequence becomes less obvious in its organization, and more impressionistic in its flow. There is a confusion of time: many of the black and white photographs in this book are flash-lit, and technically resemble pictures made from the 1950s to the 1980s, although there are plenty of clues that reveal the pictures to be made in the 21st century. The past that’s invoked in style and subject is unstable, inconsistent and amorphous. Ultimately, this may be the moral of the story: the inherited dreams of the past inform the ways that we occupy the present, in all of our uncertainty.

© Alec Soth 2015 courtesy MACK

Songs provide a thread throughout the book: snippets of lyrics of American standards rhythmically punctuate the sequence. But the lyrics are as disembodied as the uncaptioned photographs are decontextualized. Soth’s positioning of lyrics and pictures alongside one another produces a songbook that is distinctly brooding. Soth, like David Lynch, recognizes that the optimistic promises embedded in the happiest expressions of popular culture also threaten disappointment, that those dreams may fail to come true. Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks describe imaginary locales that resemble the places where Soth photographed, small American places that promise that things will get better, but where actually they will, at best, stay the same; at worst they risk dipping into madness and erasure.

Soth has a talent for creating subdued yet expressively rich photographs. His skill is both in his canny choice of subjects and in his ability to imbue his pictures with an emotional valence. He’s been doing this through his entire influential career, with formality in the slowly-paced Sleeping by the Mississippi and Niagara, and more loosely, but with no less acuity, in his more recent projects like Broken Manual. However, while his earlier projects were often heavily contextualized by ephemera, like the notebooks in Niagara where we could actually read the thoughts of his subjects, the pictures in Songbook are removed from any documentary reference.

© Alec Soth 2015 courtesy MACK

The photographs in Songbook are drawn largely, though not entirely, from the LBM Dispatches project that Alec Soth and writer Brad Zellar produced between 2012 and 2014. Soth sought to return to his small town newspaper origins and find stories that would speak to community (what have come to be known dismissively as “human interest” stories) and through them describe the quirky particularities of “middle America”. In a series of road trips, Soth and Zellar visited Ohio, Texas, New York, Georgia, California, Colorado and Michigan, producing and distributing a newspaper rapidly after their return from each location; most of the LBM Dispatches have now sold out.

The LBM Dispatches differed, though, from a community newspaper in that their primary audience was not the communities themselves, but the world outside of the America that Soth and Zellar explored. A community newspaper allows a community to tell a story about itself, but the LBM Dispatches were more in line with Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, poems that valorized small lives in a fictional town, or James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, in which the relentless documentation of the most unremarkable, seemingly ordinary details acknowledged the reality of lives lived far from the reader’s own.

© Alec Soth 2015 courtesy MACK

What’s to be made of Soth’s repurposing of his narratively grounded, journalistically contextualized work into the service of the dreamlike and overtly constructed poetic Songbook? What are the questions that Songbook addresses, what impulses does it serve, that the LBM Dispatches could not?

Songbook certainly invites comparison with Robert Frank’s seminal 1958 critique of post-war America, The Americans. Both are sprawling photographic assessments of the state of a nation that has trouble seeing its realities for its aspirations. Both books are arguments, made through the selection of subjects (ordinary, not famous people and places) and with a photographic style that uses the visible as a vehicle for conveying the poetic. Every image in both bodies of work is rich in evocative or surprising details or gestures that strengthen an overall mystique but also articulate a specific commentary.

But where The Americans was, in its time, an effort to make visible the rough and rich turf that lay beneath the glossy lawns of an invigorated American dream, Songbook is a dream of a dream (the “Song to the Siren” that Lynch uses so hauntingly in Lost Highway) a bittersweet telling of less vigorous ambitions. Songbook describes a melancholic arc couched in a notion of the American past as yet-unredeemed potential and possibility. Soth’s structured narrative imagines an American dream not as a hope or aspiration, but as a reverie.

© Alec Soth 2015 courtesy MACK

The fragility of the dream reveals itself in the last segment of the book, where memory, nostalgia, and dream blend in a slow, spiraling hallucination. It’s as though American confidence is embedded in the grain of the wood paneling and clapboard that appear repeatedly through the book, even when those panels have warped fantastically out of shape. There’s a point where nostalgia gives way to time travel: a sleeping Civil War re-enactor wearing cushioned athletic socks; a man carrying a newspaper reporting Kennedy’s assassination under his arm, the newspaper wrapped in plastic. The next to last photograph in the book, a contemporary office building gently emerging from fog, is one of the few images in the book that does not signal the past, and it looks like science fiction.

Songbook is also clearly informed by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s 1977 landmark book of reconstructed found photography, Evidence. Where Sultan and Mandel drew from industrial and institutional archives, reveling in the unintended poignancy and humor of pictures that were made for very specific practical purposes, Soth draws from his own recent archive in much the same way. What logic governed the images that he chose and the ones that he omitted? What did it feel like for him to create new meanings for these once-anchored images, to move them from being peculiar but connected to fully mysterious, possibly unknowable?

© Alec Soth 2015 courtesy MACK

Finally, there’s a sense in which Soth’s archive of his own photographs is a proxy for the history of photography. His images are populated with people and gestures that we have seen before: the language of photography has been internalized and reproduced as a mashup. Here is a blonde woman with eyeliner at the race course who could have stepped out of a Garry Winogrand photo. Here’s a view of a field of empty picnic tables that could have been made by Joe Deal. Weegee, Friedlander, and Meatyard are present, as are any number of other influences and references. When I look at Soth’s picture of a boy with a cowboy hat and cigarette, dancing with a girl whose face we can’t see, it awakens a feeling of déjà vu. I’m sure that I’ve seen a picture that felt just like this before but I can’t recall where.

Songbook’s impressive feat is the way in which Alec Soth has allowed many impulses to mingle freely in one volume. He recognizes photographs as things and ideas that can live again and again, folded into our consciousness and unconscious histories. While the book stands alone as a mysteriously beautiful narrative, its real power is in Soth’s ability to set a traditional object – the photo book – at the intersection of so many discourses. He’s not the first to make these moves, but he’s done so here fluidly and powerfully.

Note: The photographs provided by the publisher accompanying this review are the first five photographs in Songbook and are presented here in the order in which they appear in the book.

Songbook by Alec Soth published by MACK

Leo Hsu is a photographer and writer based in Toronto and Pittsburgh.

Contact Leo here.

Purchase Songbook here.